Militarism is all around us. How do you convince a population to be okay with paying so much of their taxes to the military and the police when the climate is collapsing, mental health across the United States is floundering, people are denied healthcare, and more and more of our neighbors are unhoused every year? One way is by normalizing violence through militaristic language and linguistic imperialism.

By "linguistic imperialism," we mean when colonizers impose their language and names onto the people and land they are colonizing, which promotes assimilation to the colonizers worldview, values, systems, and structures. You can find this at most U.S. military bases around the world, as well as all over your city or town.

We use "militaristic language" to mean the use of military-related terms and metaphors in everyday conversations. Doing so normalizes the militaristic ideologies and prevents us from thinking creatively about conflict and healing. Militaristic language creates a binary, you win or you lose, which keeps us from dreaming what more is possible. We are surrounded by cultural expressions of a politic obsessed with the military—it's everywhere from the way healthcare providers discuss "battling" disease, to the disproportionate presence of police and military symbols in children's media and toy aisles.

To be clear, we are writing this from the perspective of people who come from lineages of colonizers. When we speak about militarism, we are not speaking of violence done in response to occupation, state violence, ethnic cleansing, and genocide, or in self-defense of you and your loved ones by those with more political power or resources.

Now, let’s examine some of the militaristic language we're surrounded by in “Minnesota."

Linguistic Imperialism

Mni Sóta Makoce, where the water reflects the sky in Dahkóta.

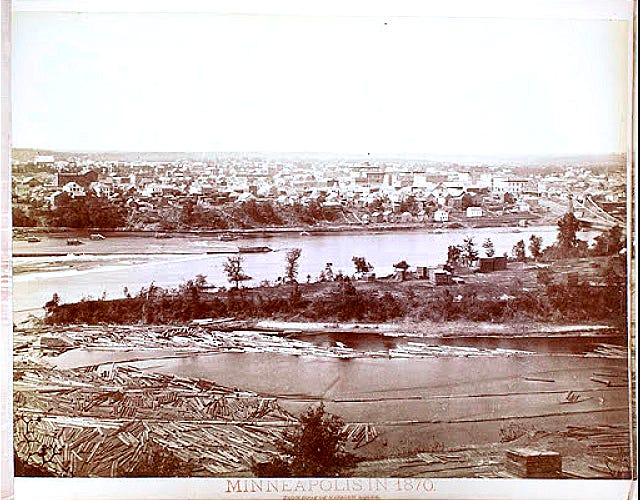

Misi Ziibi, the great river in Ojibwe, and Ȟaȟáwakpa, River of the Waterfalls in Dahkota.

Nookomis, my grandmother in Ojibwe.

These names indicate reverence, respect, and connection to the land and water.

Then colonization, genocide, and linguistic imperialism:

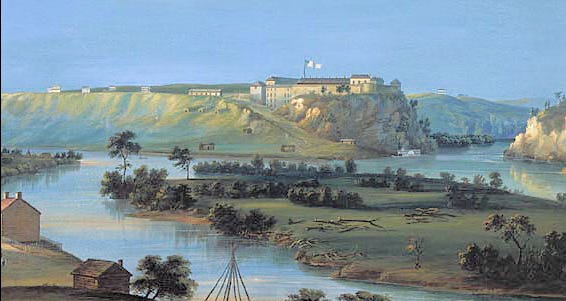

The initial land theft that occurred by the U.S. government, in what they decided to call "Minnesota," was done by the greedy guts who built Fort Snelling. Fort snelling is close to a Dakhóta sacred site, Bdóte, where two rivers converge. For some Dahkóta people, this is the site of their genesis story.

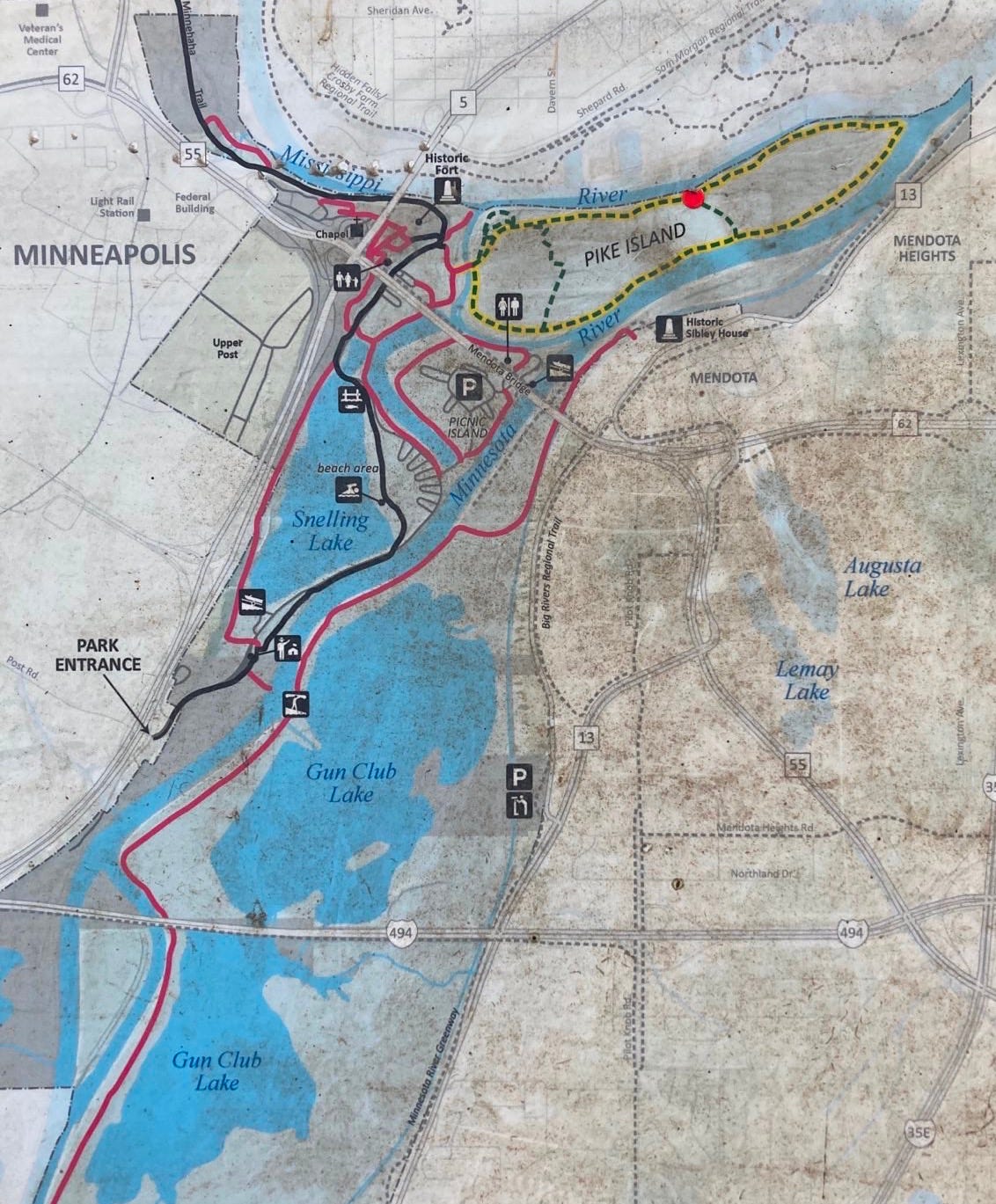

Where the Misi-ziibi (Mississippi) and the Mni Sóta (Minnesota) rivers converge, there is an island, Wita Tanka (Big Island).

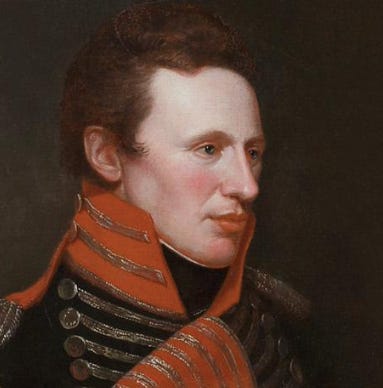

Zebulon Pike, the lieutenant who tried to make land theft and murderous displacement “legal” by going to the island to meet up with Dahkóta people and offer the deal– to sell 100,000 acres of land to them, which now make up the Twin Cities. Most Dahkóta chiefs present there didn’t sign it. The colonizers said the land was worth $200,000 but paid the Dahkóta only $2,000, and even that payment didn't take place until years later.

Sickeningly, Wita Tanka is now "officially" called Pike Island in a tribute to Zebulon Pike. His legacy of violence and manipulation is strengthened and validated each time the name is spoken or written.

South of "Pike Island" there is a lake known as "Gun Club Lake," a name that is not only insulting to the original inhabitants of this land but also absurdly on-the-nose. So many places have been renamed in the colonizers' image.

Everything renamed in their image of violence and colonization…

Powderhorn Lake

A "powderhorn" is a hollowed horn of a bull or goat to carry gunpowder in. Powderhorn Lake was named for its shape by the colonizers at Fort Snelling, who evidently couldn’t think of any more creative way to describe it.

Boom Island

Named after a barrier for logs coming downstream, extraction infrastructure of the timber used to build the new settler-colonial state.

Battle Creek Park

In an effort to justify their own genocidal policies by depicting Indigenous people as violent, colonizers named this park after an 1842 conflict between Dahkóta and Ojibwe people.

Lake Harriet

Lake Harriet was named for Harriet Lovejoy, wife of the colonizer colonel Henry Leavenworth, who founded Fort Snelling in 1819.

Through direct actions, legal challenges, and educational campaigns, Indigenous people have resisted the way that militarized language and colonialist propaganda erases their cultures and existence by militarized language and political propaganda around the world.

We are grateful to those who reminded the public of the name Bde Maka Ska and the legacy of the name Calhoun (a slave owner), which resulted in the city formally recognizing the lake's name change in 2018.

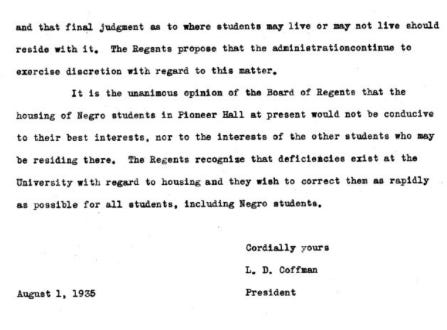

Thank you to the students who attempted to remove Coffman’s (a racist university president) name from the union at the University of Minnesota.

Thank you to the AIM members and other Indigenous people who tore down the statue of Columbus at the capital, for which they faced escalated legal charges.

This is anti-war resistance to US militarism, imperialism, and colonialism.

Militarized Language

Bomb imagery is casually evoked in this package of "Lolli Bombs," a tomato brand carried by Trader Joe's. The implications of such a brand name are insidious and a little bewildering, illustrating the absurd omnipresence of militaristic imagery in our daily lives. What exactly is the desired subliminal messaging here? Are shoppers meant to associate bombs with tomatoes? To see bombs as natural and normal?

Are tomatoes (or lollipops) supposed to be sweet enough to make us forget the images of Palestinian children with skulls torn apart in the arms of their running parents?

Who cares that the U.S. has dropped on average 46 bombs a day for twenty years?

The language we use changes the way that our brains think and process information. It is harder to approach our relationships to ourselves, each other, the rest of the living world with curiosity, love, and compassion when we have been conditioned to see every interpersonal interaction as a battleground. How much language do we all use (ourselves included) without thinking twice about its underlying militarism?

A short list of everyday, casually militaristic phrases in English

"shoot me a text"

"bullet points"

"the bomb.com"

"blow your mind"

"hit me up"

"fighting a losing battle"

"pull the trigger"

"guns blazing"

"shot myself in the foot"

"shot in the dark"

"bulletproof"

"dodged a bullet"

"line of fire"

“rapid fire”

"shoot your shot"

"tied to an idea"

"bombshell"

"shot from the hip"

"out-gunned"

"fight the good fight"

We find that we have to rephrase things often to de-militarize our language. English has developed and retained these phrases as a direct result of its legacy of violence, genocide, and colonialism. Examining our language is one small but necessary step in decolonizing our minds, rewiring our brains to prioritize mutualism and care instead of validating war.

(And while it's not our primary concern in this article, militaristic language also reinforces patriarchy and casual misogyny. Watch an excellent discussion of this by Ocean Vuong, queer Vietnamese American poet, here.)

As we do the lifelong work of unlearning our socialization in a society complacent with naming life-giving ecosystems after slave owners and comparing tomatoes to bombs, here are questions we are reflecting on:

How would the English language need to change to allow our language reflect the dreams of abolition, liberation, creation, and revolution?

What other worlds might we be able to imagine once we learn to be more creative with our word choices?

What better approaches to conflict might be possible once we stop subconsciously affirming militarism?