by Griffy LaPlante (they/them), writer-artisan in Harlem & Minneapolis, author of “Epistolary Griffy”

Linocut illustration of Staughton Lynd by Minneapolis caricature artist Ray Gorlin

1.

In spring 2024—6 months or so into Israel’s escalation of its genocide against the Palestinian people—my friends and I became fascinated with the Honeywell Project.1

2.

The Honeywell Project was a group of people in Minnesota who organized against the Honeywell Corporation in the 1970s and ‘80s. Honeywell Co. was (and still is) a MN-based manufacturer and a military contractor. At the time, it was manufacturing the cluster bombs the U.S. was dropping in the Vietnam War.

3.

As I did my research, I kept noticing references to a certain article by the socialist organizer and lawyer Staughton Lynd written in 1968 (13 years into the Vietnam War). The Honeywell Project founders cited this article as their inspiration for starting their group.

4.

But although writings by Lynd—who died just two years ago, at the age of 92—are widely accessible on the internet, I could not find this article anywhere. According to the references to it I’d found, Lynd used this article to make a passionate, persuasive case for the next stage of the Vietnam War protest movement to focus its activism on weapons manufacturers (instead of lawmakers), which is ultimately what the Honeywell Project spent the next 20 years doing.

5.

I did, however, read in several places that the article in question was published in the October 1968 issue of Liberation. The magazine was long out of print, but as I kept digging I was pleased to discover that several of its issues had been collected and preserved by a purveyor of movement ephemera in San Francisco called Bolerium Books. When I visited their website, I was even more thrilled to see that they had the October 1968 issue, and for sale.

6.

I ordered it right away. You might be wondering, as I wondered myself: Why was I so determined to find this article? At first, I was motivated mostly by my desire to solve the problem, to see if this elusive thing could, in fact, be tracked down. But once I was checking my mailbox every day, I realized my desire had transfigured into something else. Soon I might take up in my hands a copy of the same magazine that inspired a group of plucky, peace-hungry Minnesotans over half a century ago to reorient their whole lives around a hypothesis: that a committed- and organized-enough group of people, acting out their opposition to a monstrous enemy over the long haul, might not only win their demands but might also live worthy lives in the process. They might recover the bonds of camaraderie and dignified struggle typically denied to us under imperial capitalism, bonds which are all of our rights by birth. And I wondered if this article could do the same thing to me, my friends, my comrades, and our neighbors, 55 years later.

7.

The October 1968 issue arrived on my porch in mint condition and encased in an absurdity of wrappings, bringing to mind the care and fastidiousness of a vintage and highly valuable baseball card. When I opened it, I was disappointed not to see anything written by Lynd listed in the Table of Contents, even though he was one of the editors of the publication at large. Still I read it, cover to cover, and in it I found report-backs on the Battle of Chicago describing it alternately as “action theatre,” “the drifting revolution,” and “a middle-class revolt against the tyranny of the working class,” as well as an uncannily relevant letter to the editor critiquing contemporary discourse on violence and nonviolence. I took pleasure encountering all of it, but the Table of Contents wasn’t lying—there was no article on the anti-war movement by Staughton Lynd. The mystery deepened.

8.

(It might be relevant to mention that I have a long-held affinity for things—objects, texts, ideas—whose provenances are incorrectly cited. My misattributions, as I think of them. I’ve written one essay and one poem about them already, and here I am, writing about them again.)

9.

So I retraced my steps. It seemed highly likely that the publication name was correct—it was edited by Lynd, after all, and full of reporting and opinion pieces on war resistance—so it stood to reason that the mistake lay in the issue number. Since the magazine has never been digitized, at least not on any platform I could find, I couldn’t know for sure which issue might have had it. But I knew some people who might.

Dear good folks at Bolerium,

Hello! My name is Griffy LaPlante. I’m an organizer currently based in Minneapolis.

I am working with some comrades on a public history project about the Honeywell Project, a Minnesota-based war resistance effort from the late 60s to the late 80s that focused its effort on resisting the Honeywell corporation, which was making cluster bombs out of Plymouth, MN. In our research, we have found vague references to a Staughton Lynd article that inspired the founders of Honeywell Project to take on a local war profiteering corporation. Supposedly, this article ran in the October 1968 issue of Liberation magazine. I recently ordered this magazine from you—it is wonderful and I’m thrilled to have it, but it does not appear to contain the article we're searching for.

I’m curious if you have any information about 1) whether such an article exists (written by Staughton Lynd, sometime in the late 1960s, encouraging war resisters to take on war profiteering corporations directly) and 2) whether it is actually in Liberation magazine and 3) if so, which issue. We cannot find any internet archive of it. Any information you have would be most helpful.

1 hour and 4 minutes later, I received this response:

Hi Griffy,

Thanks for reaching out-- I've taken a look into these two issues of Liberation that you mentioned and I believe I've found the referenced Lynd article in Vol 14 No 9, Dec 1969.

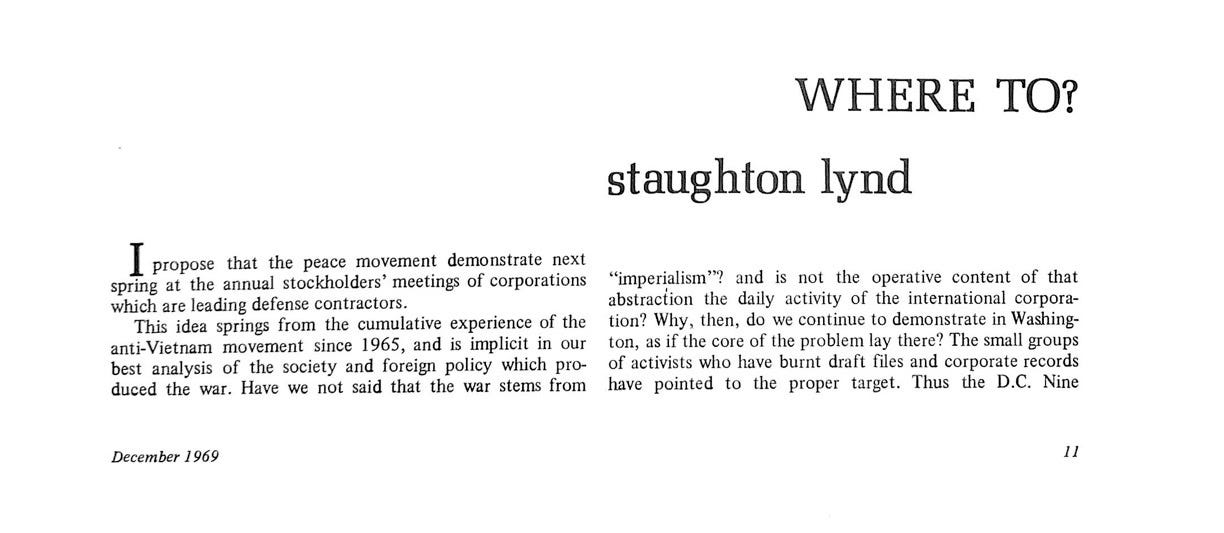

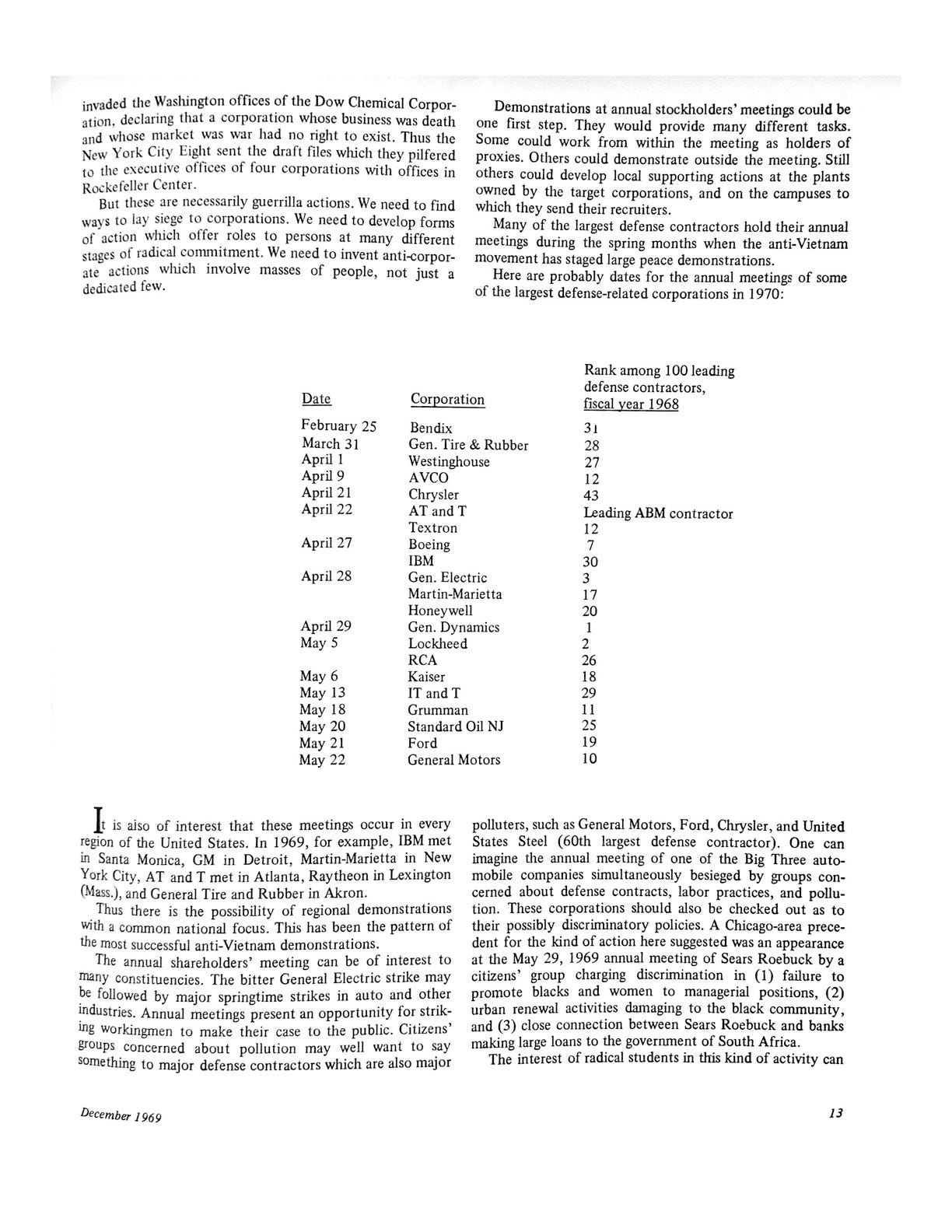

Inside, Lynd has a portion of a symposium called "The Anti-War Movement: Where To?" where he proposes that the peace movement demonstrate 'next spring' at the annual stockholders' meetings of corporations which are leading defense contractors. He seems to go on to enumerate the ways that resistance to war profiteering corporations would be the most advisable step for the anti war movement to take, and later lists dates of the annual meetings of some of the largest defense-related corporations in 1970, among much else.

Hope this helps,

Will, Bolerium Books

A week or so later, the December 1969 issue of Liberation arrived. Item number 3 on the Table of Contents: “The Anti-War Movement: Where To?”, an assemblage of three perspectives by Jeremy Brecher, Jack Newfield, and Staughton Lynd.

10.

The article, it turned out, was short and to the point—Lynd encouraged readers and their peacenik friends to target corporations with military contracts at their upcoming shareholders meetings, the dates and locations of which he included for easy reference. Was it life-changing? Paradigm-shifting? Not especially to me. Perhaps because we’ve already learned the lesson he wrote this article to impart, and upon rediscovery it was unlikely to usher in a new era of protest the way it did then. Possibly because the state of things (lives, paradigms) have changed in the intervening half-century since he wrote it. I mean—haven’t they? Surely they have, although I admit it’s not always clear to me how, because here we are, in the year of dead CEOs and the Māori haka as protest on New Zealand’s parliamentary floor, and U.S.-based corporations still stoke, fund, and profit off proxy wars being waged all over the world. Thus far, the majority of protests against all that—that we know of—have been directed solely at elected officials, or at nobody at all.

Still: I am hoping that is not the whole story, or at least not the end of it.

I realized only after finding Lynd’s article how much I was hoping it would contain commandments; I wanted its author, like a white Jesus, to save us. Instead, I read it and discovered that not only was it commandmentless—not only was Staughton Lynd not a savior (and would probably have rolled over in his grave if he knew I wanted him to be)—but there are not likely to be any other such shortcuts forthcoming, no deus ex machina in this modern, ancient struggle.

Moreover, now that I had the article, I had no idea what to do with it, modest little history-jewel that it was. The historian Brent Hayes Edwards writes of the anxiety that comes along with discovering what you were looking for while still fearing that the object of your successful pursuit will remain “recalcitrant, even gnomic [unhelpfully ambiguous], a lump that cannot be placed into anything approaching historical intelligibility”—a dead end.2 I sympathized. My initial idea—to simply reprint the article in full—was no good; it was too historically-specific and logistical for that. What’s my name, Staughton, what’s my station?3 I wrote this to try to find out.

Wikipedia provides a great overview of the Honeywell Project: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honeywell_Project

Brent Hayes Edwards, “The Taste of the Archive” (Callaloo, Vol. 35, No. 4, Fall 2012, pp. 944-972)

“What's my name, what's my station? Oh, just tell me what I should do /

I don't need to be kind to the armies of night that would do such injustice to you /

Or bow down and be grateful and say, ‘Sure, take all that you see’ /

To the men who move only in dimly-lit halls and determine my future for me” /

—Fleet Foxes, “Helplessness Blues” (song and album released in 2011)